How the Semiconductor Supply Chain Traveled the World and Why It Is Finding Its Way Back

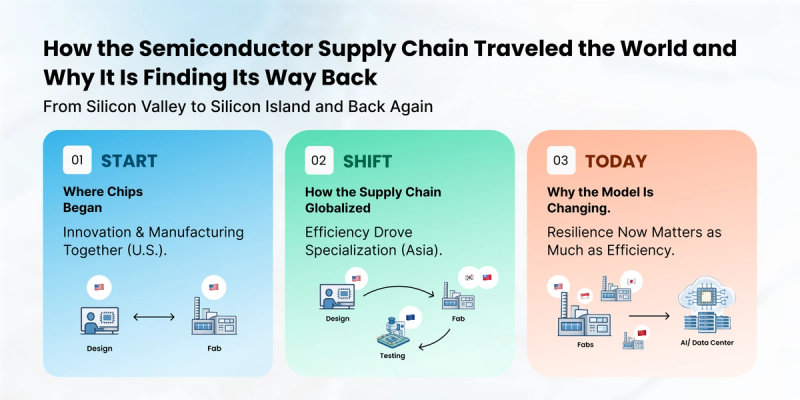

Semiconductor chips are created through many connected steps. Chip design, manufacturing, testing, packaging, and validation all depend on one another. These steps often happen across countries at specialized companies. The final chip reflects careful coordination across a global network working together with high precision.This complexity explains why the global semiconductor supply chain did not simply grow global. It became deeply interdependent.

Today, as artificial intelligence (AI), electric vehicles, 5G infrastructure, and cloud computing drive unprecedented demand, the industry faces a critical question: Why did semiconductor manufacturing move from the U.S. to Asia and why does it now make sense to bring parts of it back?

To understand this, we need to follow the industry as a series of decisions, real world constraints, and strategic consequences.

How It Started: Innovation and Manufacturing Under One Roof

In the decades after World War II, the United States didn’t just invent semiconductor technology, it made it locally. Institutions like Bell Labs, and companies such as Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, didn’t separate design from manufacturing. They were vertically integrated: engineers in California and Texas were designing circuits one day and standing next to the machines that turned those designs into silicon the next.

At the time, fabs (the specialized plants where chips are made) were expensive but manageable. Process technologies were simpler, and the industry was still emerging. In this context, design and manufacturing worked best when they were close together, making the process both efficient and reliable.

How the U.S. and Asia Began a Shared Semiconductor Journey

In the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. semiconductor industry faced a turning point. Building and running cutting edge semiconductor manufacturing facilities, especially assembly and testing, became increasingly expensive and complex, requiring huge capital investment and labour intensive work. Many U.S. companies began focusing on chip design and innovation, which offered higher returns and less capital risk than owning large fabrication plants. U.S. industry leaders and policymakers started encouraging global partnerships in manufacturing, especially with Asian economies that were much more economical and eager to grow their own technology sectors.

For the United States, supporting semiconductor development in countries like Japan and Taiwan created economic opportunities and strengthened strategic alliances in a rapidly globalizing world. U.S. firms benefited by licensing design expertise, semiconductor equipment, and intellectual property while focusing on research, software, and design leadership. This approach also helped American companies stay competitive in a period of rising international competition.

Across the Pacific, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan had strong incentives to build their own semiconductor industries. Governments in these regions saw semiconductors as an engine of economic growth and global technological relevance. In Japan, coordinated industry efforts backed by government programs helped companies like Fujitsu and NEC achieve breakthroughs in chip fabrication and production scale in the 1970s.

In Taiwan, a sequence of early policy decisions and investments laid a foundation for long term growth. Projects such as technology transfer agreements and the establishment of specialized research institutes helped the island transition from low technology exports to advanced manufacturing. The founding of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in 1987 became a defining moment in the global industry, enabling Taiwan to focus on highly specialized chip production based on close ties with Silicon Valley engineers and U.S. design firms.

For South Korea, strategic government support and coordinated industrial policies helped firms such as Samsung and SK Hynix expand rapidly, especially in memory chip production, where South Korea now accounts for a dominant global share. Combined with tax incentives and export support, these moves allowed Asian countries to grow their semiconductor capabilities both economically and politically, strengthening national competitiveness on the world stage.

As a result of these shifts, manufacturing capabilities in Asia grew faster than many early participants expected. Taiwan and South Korea became leaders in advanced fabrication and memory chips, while Japan maintained strong positions in materials and equipment. This growth reshaped the global semiconductor supply chain and gradually reduced the proportion of manufacturing done in the United States, even as American companies continued to lead in chip design and innovation.

Over time, this model delivered enormous gains. Chips became cheaper, faster, and more powerful. Supply chains became tightly tuned for cost and efficiency. But there was a drawback: dependence. By mid-2025, TSMC alone had captured roughly 70% of global foundry revenue, especially in leading-edge technologies critical to AI and high performance computing. That level of concentration brought efficiency, but also vulnerability.

When the System Stretched Too Thin

A series of shocks made the world painfully aware of semiconductor dependency:

- Trade tensions between the U.S. and China constrained China’s access to advanced chips and production tools.

- Global shortages (2020–2023) showed how quickly tight supply could disrupt whole industries, from cars to consumer electronics.

- The pandemic shut down key facilities and broke logistics links that were taken for granted.

Moreover, advanced chips have become national assets in geopolitical competition. Capabilities in AI, defense systems, space technologies, and communications infrastructure all rely on reliable access to state-of-the-art silicon.

As a response, governments, especially the U.S. actively began incentivizing domestic fabs.The centerpiece of this shift was the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act, which provides tens of billions in subsidies and tax credits to bring semiconductor manufacturing back onshore and strengthen domestic capabilities.

A Confluence of Strategy and Commerce

One of the most striking stories of this new era is how TSMC, the industry’s largest contract manufacturer, is building significant capacity in the United States. In Arizona, the company began its expansion in 2020 with a $12 billion investment in a manufacturing plant in Phoenix, aiming to bring advanced production closer to customers like Apple, Nvidia, AMD, and Qualcomm. Since then, investments have grown to over $65 billion, including land acquisitions for a cluster of fabs, packaging facilities, and research capabilities. The site has entered early production phases for advanced nodes, marking a symbolic milestone in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing.

This is not TSMC’s first attempt at large-scale manufacturing outside Taiwan. Earlier efforts in the U.S. faced higher construction and operating costs, longer permitting timelines, a limited pool of skilled workers, and complex logistics for critical inputs such as specialized chemicals. As a result, it was more economical and feasible for TSMC to concentrate its most advanced manufacturing in Taiwan, where the surrounding ecosystem reduced cost, complexity, and execution risk.

The centerpiece of that success was Hsinchu Science Park, a coordinated industrial ecosystem established in the 1980s that brought together government support, universities, and suppliers. The park helped TSMC scale rapidly by providing streamlined infrastructure, skilled engineers, supportive regulations, and close collaboration with partners, creating one of the world’s most advanced semiconductor hubs.

Today, several factors make U.S. expansion more promising. Policy support through the CHIPS and Science Act has narrowed cost and talent gaps, while investments in workforce development and regional supply chains, including advanced packaging, strengthen the ecosystem around new fabs. Manufacturing in the U.S. remains more expensive than in Taiwan, and long-term success will depend on achieving comparable yields, reliability, and process learning rates. TSMC’s expansion is part of a broader trend, including Intel and Samsung’s investments in the U.S. and similar initiatives in Europe and Japan, reflecting the recognition that geographic concentration of advanced chip manufacturing is a systemic risk. The goal is not to replace Taiwan’s role, but to add redundancy and resilience to the global supply chain while balancing efficiency and strategic control.

Redrawing the Map While Keeping the World Connected

The global semiconductor ecosystem operates as a deeply interconnected network, with each region specialising in critical stages of the value chain.U.S. companies continue to lead in chip design, generating the majority of global semiconductor intellectual property and electronic design automation innovation. Taiwan remains the center of gravity for advanced semiconductor manufacturing, producing over 90 percent of the world’s leading‑edge logic chips. South Korea anchors the memory market, while Europe, Japan, and Southeast Asia provide essential support through materials, manufacturing equipment, packaging, and testing. China plays a critical role across multiple layers of the supply chain. It dominates raw materials and processing, including silicon wafers, specialty chemicals, and rare earths, and has substantial mature-node wafer production (≥28nm), which supports analogue circuits, automotive electronics, and consumer devices.

What has changed is the industry’s tolerance for concentration. There is a growing realization that if a single region supplies most of the world’s most advanced chips, even a short disruption can ripple across cloud infrastructure, automotive production, and consumer electronics within weeks. Therefore, companies and governments are investing tens of billions of dollars to add geographic redundancy into the system and avoid single points of failure.

This marks a subtle but important shift in mindset. For decades, success in semiconductors meant pushing efficiency to its limits. Today, success increasingly means balancing efficiency with resilience, speed with stability, and scale with control.